Programmatoelichting 'De Staat'

Item

-

name

-

nl

Programmatoelichting 'De Staat'

-

headline

-

en

Program notes 'De Staat'

-

nl

Programmatoelichting 'De Staat'

-

creator

-

Louis Andriessen

-

articleBody

-

en

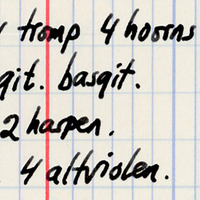

I wrote De Staat (The Republic) as a contribution to the discussion about the place of music in politics. To keep the issues straight it is necessary to differentiate between three aspects of the social phenomenon called music: 1) its conception (devising and planning by the composer); 2) its prduction (performance); and 3) its consumption. Production and consumption are by definition if not political then at least social. The situation is more intricate when it comes to the actual composing. Many composers feel that the act of composing is ‘suprasocial’. <br><br>I don’t agree. How you arrange your musical material, what you do with it, the techniques you use, the instruments you score for, all of this is determined to a large extent by your own social circumstances, your education, environment and listening experience, and the availability – or non-availability – of symphony orchestras and government grants. The only point on which I agree with the liberal idealists is that abstract musical material – pitch, duration and rhythm – is suprasocial: it is part of nature. There is no such thing as a fascist dominant seventh. The moment the musical material is ordered, however, it becomes culture and, as such, a given social fact.<br/><br/>I decided to draw upon Plato to illustrate what I mean. Everyone sees the absurdity of Plato’s statement that the Mixolydian mode should be banned because of its damaging effect on the development of character. It is equally clear that he was confusing the issue in wanting to ban dulcimers and the craftsmen who made them from his ideal state. What he wished to ban was the social effect of the music played on them, something similar perhaps to the ‘demoralising nature’ of the Rolling Stones’ concerts.<br/><br/>My second reason for writing De Staat is in direct contradiction to the first. Perhaps I regret the fact that Plato was wrong: if only it were true that musical innovation represented a danger to the State! When Bertolt Brecht returned to Europe after the war he chose to settle in East Germany. The first play he wrote there was censored by the party. But Brecht said to the assembled Western journalists, ‘In what Western country would the government take the time and trouble to spend thirty hours discussing my plays with me?’ De Staat has nothing to do with Greek music, except perhaps for the use of oboes and harps and for the fact that the entire work is based on tetrachords, groups of four notes, which also explains the scoring for groups of four instruments.<br/><br/>Just before the final choral section the orchestra splits into two identical halves, as announced earlier in the work. They play two melodies which sound like one because their rhythms are complementary (the performers play one after the other). Polyrhythm is introduced for the first time in the coda following the choral finale, with the two orchestras each playing their own separate score. But this time they have the same melody, a canon. Finally, in the last bars, they attain the homophony introduced shortly after the opening choral section. I regard this as the major subject of the work.<br/><br/> Louis Andriessen, 1976

-

nl

De Staat heb ik geschreven om een bijdrage te leveren aan de discussie over wat muziek met politiek te maken heeft. Om de discussie enigszins helder te kunnen voeren is het noodzakelijk het maatschappelijk verschijnsel dat muziek heet te verdelen in drie aspekten: 1. de conceptie (het bedenken en ordenen door de componist), 2. de productie (het spelen van het stuk) en 3. de consumptie van muziek. Het is duidelijk dat productie en consumptie per definitie een zo niet politiek, dan toch zeker een maatschappelijk gegeven zijn. Met het componeren zelf ligt het ingewikkelder. Veel componisten denken dat het componeren als bezigheid een "bovenmaatschappelijk" gegeven is.<br><br>\nIk bestrijd dat. Hoe je muzikaal materiaal ordent, op welke manier, van welke technieken je gebruik maakt, voor welke instrumenten je schrijft, wordt, althans voor een zeer belangrijk deel, bepaald door je eigen maatschappelijke omstandigheden, door je opvoeding, milieu, luisterervaringen, door het al of niet aanwezig zijn van symfonieorkesten en subsidiegelden. Het enige wat ik met de liberale idealisten eens ben, is dat het abstracte muzikale materiaal – toonhoogte, duur en ritme – "bovenmaatschappelijk" is: het is in de natuur. Er bestaan geen fascistische septiemakkoorden. Zo gauw het muzikale materiaal geordend wordt is het echter cultuur, en is het een maatschappelijk gegeven. <br><br>\nDat ik deze teksten van Plato gebruikt heb, is om het bovenstaande te verduidelijken. Iedereen ziet het belachelijke in van Plato's uitspraak dat de mixolydische toonladder moet worden afgeschaft omdat ze een slechte invloed zou hebben op de karaktervorming. Iedereen zal begrijpen dat Plato de zaken verwart als hij snaarinstrumenten* en hun bouwers uit de staat wil weren. Wat Plato wilde weren was het maatschappelijk effect van de muziek die op snaarinstrumenten* gespeeld werd; misschien enigszins te vergelijken met het z.g. "zedenbedervende karakter" van de Rolling Stones-concerten. <br><br>\nDe tweede reden waarom ik de Staat heb geschreven is met de eerste direkt in tegenspraak: ik betreur het misschien wel dat Plato geen gelijk heeft: was het maar waar dat muzikale vernieuwing staatsgevaarlijk is. Bertolt Brecht verkoos na de oorlog de DDR als land om in terug te keren. Zijn eerste toneelstuk werd direkt al gecensureerd door de partij. Maar Brecht zei tot de toegestroomde journalisten: "Waar in het westen vindt de overheid het belangrijk om 30 uur met mij over mijn stukken te praten?" <br><br>\nMet griekse muziek heeft De Staat niets te maken, behalve misschien het gebruik van hobo's en harpen en het feit dat het gehele stuk is gebaseerd op tetrachorden: groepen van vier tonen. Daaruit is ook de bezetting van groepen van vier ontstaan. Voor het slotkoor splitst het orkest zich in twee identieke orkesten (al eerder in het stuk aangekondigd). Zij spelen twee melodieën, maar het lijkt er één, omdat het ritme complementair is (men speelt om de beurt). Pas na het slotkoor in de coda komt voor het eerst in het stuk polyritmiek voor: de twee orkesten spelen elk een zelfstandige partij. Maar hier is het dezelfde melodie: het is een canon. In de laatste maten wordt de eenstemmigheid bereikt die vlak na het openingskoor geïntroduceerd is en die ik beschouw als het belangrijkste muzikale onderwerp van het stuk. <br><br>\n* Er stond oorspronkelijk 'pektiden', dat verwant is met het Griekse πέϰω kammen, vandaar: 'gekamde instrumenten'. Omwille van de begrijpelijkheid is hier twee maal gekozen voor 'snaarinstrumenten' (red.). <br><br>\nLouis Andriessen, lp <i>De Staat</i>, Donemus CV 7702

-

Identifier

-

ark:/23946/b5PC23

Linked resources

Items with "is work commentary in: Programmatoelichting 'De Staat'"

| Title |

Class |

De Staat De Staat |

work

|

De Staat

De Staat

De Staat

De Staat