Being Where?

“Did I try everything, ferret in every hold, secretly, silently, patiently, listening? I'm in earnest, as so often, I'd like to be sure I left no stone unturned before reporting me missing and giving up,” read the first lines of Beckett's Text for Nothing no.7. In this text, a narrator describes himself sitting on a bench in a small railway station, waiting for nothing. Trains and time pass while his mind is absent, floating elsewhere, performing what Hugh Kenn has called fantasies of non-being. The narrating subject in Text for Nothing no. 7 inhabits a curiously located space in which the subject is at an ontological or at least psychological distance from itself.

In 1986, Beppie Blankert presented a staging of Beckett's text titled Double Track. Playing with a huge mirror, she turns the question of the subject's location into a riddle for the spectator. Spectators find themselves located between two raised stages. On the stage in front, a mirror shows the reflection of a dancer. This dancer is actually present on the stage behind the spectator, sitting on a bench, waiting, like the character in Beckett's story.

The spatial setup of the performance reminds me of Plato's famous story of the humans in the cave who watch mere reflections of what is actually present behind their heads. However, unlike the people stuck in the cave and deceived by mere shadows on the wall, spectators of Double Track know what they see in front is a reflection. When this spectator enters the theatre, both the mirror in front and the stage behind the auditorium are fully lit, and the dancer can be seen on the stage behind, sitting on the bench. Furthermore, the mirror exposes, apart from the dancer, someone else's presence as well - someone who remains in the dark in Plato's scenario - and this is the spectator. The mirror exposes the spectator's body as the locus of looking and illuminates how this body gets positioned within the 'architecture" of the theatrical event.

“is that me still waiting, sitting up at the edge of the seat, knowing the dangers of laisser-aller, hands on thighs, ticket between finger and thumb, in that great room dim with the platform gloom as dispensed by the quarter glass self-closing door locked up in those shadows, it's there, it's me.”

Beckett's text confronts the reader with a merely disembodied voice speaking of itself to itself. In his text, this disembodiment is related to a particular type of vision “as if from Sirius” and opposed to this heap of flesh sitting over here in the railway station. This separation of the mind from the "heap of flesh” allows the mind to travel elsewhere while, in fact, “I had not stirred hand or foot from the third class waiting room of the South-Eastern Railway Terminus.”

In Blankert’s performance, Becket's text ’migrates' from the domain of text-based theatre to dance. This move sheds new light on questions of traveling, tracking movement, and positioning, as Beckett brings them up in his text. Train travel turns into a metaphor for navigating attention through performance, and the ’architecture’ of this performance into a positioning system defining where and how we, the audience, are. Double Track exposes the spectator as a body at the center of a theatrical apparatus constructed to play along with the desire to leave this “heap of flesh” and enter the other worlds imagined behind the shiny glass screen that separates the spectator from the world projected over there. Double Track also shapes our awareness of how such traveling into absent worlds involves a position for the spectator at a certain distance from him or herself as the body. Absorbed in the object of their attention, these bodies seeing and theorizing about what is seen on stage are conspicuous by their absence.

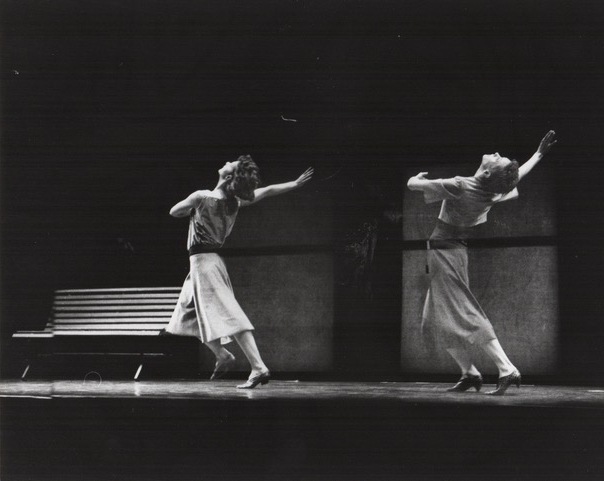

Through the mirror, the presence of the dancer is split up. Two video monitors on the stage in front of the audience take the splitting up one step further. They show the very same dancer sitting on a similar bench at a small railway station, waiting for nothing. Then, this dancer splits in two as well. That is, the dancer - wearing a light costume - is sitting on the bench and remains seated, while at the same time, another dancer in a dark costume rises from where the man in white is sitting and walks away. As it appears, this second person had actually been seated on a similar bench behind the mirror, invisible to the audience. Invisible, that is, until the light behind the mirror goes up. Through the see-through mirror, the two dancers perform a duet that actually takes place in two different locations - they are on two different stages - one in front and one behind the audience. The dancer in front is seen through the mirror, while the one behind is seen reflected in the mirror. Often, it is hard to say who is where. Sometimes they are together behind the mirror in front, sometimes behind your back, sometimes together on the same stage, sometimes not. When the two dancers perform a duet, the sound of their feet - coming from two different directions - undercuts the unity presented by the visual image. The audience, eager to 'get the picture', is destined to lose track.

With this striking image of the 'difference within,' Double Track undermines the logic of the unity of space as well as the unity of the subject perceiving. The performance shows these unities to be the product of our involvement with the world through different perceptual systems simultaneously and depending on a body that is the locus of the connections of these perceptual systems. Furthermore, the performance shows unity as perceived in the mirror as the product of bodily practices of perceiving that produce it at the cost of signs of difference. Although we in the audience are reminded repeatedly of the fact that the dancers are actually in different places, it appears hard to see them as such. This “heap of flesh” that we are appears to be conditioned to perceive in ways that support the duality of unitary vision and a unitary point of view, even if that means that the heap of flesh has to compensate for differences that threaten to undermine its unity. Double Track self-consciously confronts viewers with these tendencies, drawing attention to how this “heap of flesh” has been conditioned to perceive in the wake of historically and culturally specific parameters that support the tendency to leave it and travel elsewhere in thought, when, in fact, “I had not moved a hand or a foot from the third class waiting room of the South-Eastern Railway Terminus.”

Excerpt from an essay by Prof. Dr. Maaike Bleeker, published in Performance Research 6(3), 2001

“Heb ik alles geprobeerd, overal goed gezocht, stilletjes, geduldig luisterend, zonder leven te maken? Ik meen het in ernst, zoals zo vaak, ik zou er zeker van willen zijn dat ik geen middel onbeproefd heb gelaten, voor ik mezelf als vermist opgeef, en het opgeef”, lezen we in de eerste regels van Becketts Text for Nothing nr. 7. In deze tekst beschrijft een verteller zichzelf zittend op een bankje in een klein treinstation, wachtend op niets. Treinen en tijd trekken voorbij terwijl zijn geest afwezig is, ergens in wat Hugh Kenner fantasieën van niet-zijn heeft genoemd. De plek waar de verteller in Text for Nothing nr. 7 zich bevindt is een wonderlijke ruimte: een ruimte waarin het subject zich op een ontologische of op zijn minst psychologische afstand van zichzelf bevindt.

In 1986 presenteerde Beppie Blankert een enscenering van Becketts tekst getiteld Dubbelspoor. Spelend met een enorme spiegel maakt ze deze ruimte een raadsel voor de toeschouwer. De toeschouwer bevindt zich tussen twee verhoogde podia. Op het podium vooraan toont een spiegel de weerspiegeling van een danser. Deze danser is daadwerkelijk aanwezig op het podium achter de toeschouwer, zittend op een bankje, wachtend, net als het personage in Becketts verhaal.

De ruimtelijke opzet van de voorstelling doet denken aan Plato's beroemde verhaal over de mensen in de grot die kijken naar weerspiegelingen van wat zich feitelijke achter hun hoofd bevindt. Echter, in tegenstelling tot de mensen die vastzitten in de grot en misleid worden door louter schaduwen op de muur, weet de toeschouwer van Dubbelspoor dat wat hij of zij voor zich ziet een weerspiegeling is. Wanneer deze toeschouwer het theater betreedt, zijn zowel de spiegel voor als het podium achter het auditorium volledig verlicht en is de danser te zien op het podium achter, zittend op de bank. Bovendien onthult de spiegel, naast de danser, ook de aanwezigheid van iemand anders - iemand die in Plato's scenario in het donker blijft - en dit is de toeschouwer. De spiegel onthult het lichaam van de toeschouwer als de locus van het kijken en hoe dit lichaam wordt gepositioneerd binnen de 'architectuur' van het theatrale evenement.

“Ben ik dat nog steeds, die daar stijf rechtop op het puntje van de bank zit, handen op de dijen, omdat hij beseft hoe gevaarlijk het is zich te laten gaan, kaartje tussen duim en wijsvinger, in die grote zaal, slechts schaars verlicht door het droefgeestige licht op de perrons, een deur met kleine ruitjes, die automatisch dicht valt, opgesloten, in het donker, daar is het, dat ben ik.”

Becketts tekst confronteert de lezer met een ontlichaamde stem die over zichzelf tot zichzelf spreekt. In de tekst is deze ontlichaming gerelateerd aan een bepaald type visioen 'vanaf Sirius bekeken', en tegengesteld aan deze “hoop vlees” die hier op het treinstation zit. Deze scheiding van de geest van de “hoop vlees” stelt de geest in staat om ergens anders heen te reizen, terwijl in feite “ik geen hand of voet had bewogen uit de wachtkamer van de derde klas van het South-Eastern Railway Terminus”.

In Blankerts performance 'migreert' Beckets tekst van het domein van teksttheater naar dans. Dit werpt nieuw licht op vragen over reizen, het volgen van beweging en positionering zoals die door Beckett in zijn tekst worden aangehaald. Treinreizen zoals geïntroduceerd in de tekst verandert in een metafoor voor het navigeren van de aandacht door een performance, en de 'architectuur' van deze performance in een positioneringssysteem dat definieert waar en hoe wij, het publiek, zijn. Dubbelspoor plaatst de toeschouwer als lichaam in het centrum van een theatraal apparaat dat is geconstrueerd om te spelen met het verlangen van de toeschouwer om deze “hoop vlees” te verlaten en andere werelden te betreden die zij zich voorstelt achter het glimmende glazen projectiescherm scherm van de verbeelding. Dit reizen naar afwezige werelden distantieert de toeschouwer van hem of haarzelf als lichaam, zo laat Dubbelspoor zien. Verzonken in het object van hun aandacht zijn deze lichamen, die zien en theoretiseren over wat er op het podium wordt gezien, opvallend afwezig.

Door het gebruik van de spiegel wordt de aanwezigheid van de danser opgesplitst. Twee videomonitoren op het podium voor het publiek brengen de opsplitsing nog een stap verder. Ze tonen dezelfde danser die op een soortgelijk bankje op een klein treinstation zit, wachtend op niets. Vervolgens splitst deze danser zich ook in tweeën. Dat wil zeggen, de danser - gekleed in een licht kostuum - zit op het bankje en blijft zitten, terwijl tegelijkertijd een andere danser in een donker kostuum opstaat van waar de man in het wit zit, en wegloopt. Deze tweede persoon zat in werkelijkheid op een soortgelijk bankje achter de spiegel, onzichtbaar voor het publiek. Onzichtbaar, dat wil zeggen, totdat het licht achter de spiegel opgaat. Door de doorzichtige spiegel voeren de twee dansers een duet uit dat zich in werkelijkheid op twee verschillende locaties afspeelt - ze staan op twee verschillende podia - één voor en één achter het publiek. De ene danser zien we door de spiegel voor ons heen terwijl we de danser achter ons weerspiegeld zien in de spiegel voor ons. Vaak is het moeilijk te zeggen wie waar is. Soms staan ze samen achter de spiegel voor je, soms staan ze allebei achter het publiek, soms staan ze samen op hetzelfde podium, soms niet. Als gevolg hiervan wordt het publiek elke keer anders 'gepositioneerd', en vaak ook op verschillende wijze gepositioneerd in de visuele en de auditieve ruimte. Wanneer de man die je voor je in de spiegel ziet begint te praten, is zijn stem van achteren te horen. Wanneer de twee dansers een duet uitvoeren, ondermijnt het geluid van hun voeten - afkomstig van twee verschillende richtingen - de eenheid die het visuele beeld presenteert. Het publiek, dat graag 'het plaatje wil zien', is gedoemd om het spoor bijster te raken.

Met dit opvallende beeld van het 'verschil binnenin' ondermijnt Dubbelspoor de logica van de eenheid van de ruimte en de eenheid van het subject dat waarneemt. De performance laat zien dat deze eenheden het product zijn van hoe we ons via verschillende waarnemingssystemen tegelijkertijd tot de wereld om ons heen verhouden en dat ons lichaam deze met elkaar verbindt. Bovendien laat de performance zien dat ons lichaam eenheid produceert ten koste van tekenen van verschil. Hoewel wij in het publiek herhaaldelijk worden herinnerd aan het feit dat de dansers zich in feite op verschillende plaatsen bevinden, blijkt het moeilijk om ze als zodanig waar te nemen. De “hoop vlees” die wij zijn lijkt geconditioneerd om de wereld als eenheid waar te nemen vanuit een eenduidige positie als waarnemer, zelfs als dat betekent dat deze “hoop vlees” dan verschillen moet compenseren die deze eenheden dreigen te ondermijnen. Double Track confronteert kijkers zelfbewust met deze tendensen en vestigt de aandacht op hoe deze ‘hoop vlees’ geconditioneerd is om waar te nemen in het kielzog van historisch en cultureel specifieke parameters die de neiging ondersteunen om het te verlaten en in gedachten ergens anders heen te reizen, terwijl in feite “ik geen hand of voet had bewogen uit de wachtkamer van de derde klas van het South-Eastern Railway Terminus”.

Fragment uit een essay van Prof. Dr. Maaike Bleeker, gepubliceerd in Performance Research 6(3), © Taylor & Francis Ltd. 2001